Efficient Transfinite Lists

My last two posts were about ordinals and pure lists, and they got a combined whopping 11 claps, so I’m selling out and writing a post about both. In particular, this post is about a data structure I discovered for lists of transfinite length. A repo is linked at the bottom.

Definitions

So what is a transfinite list? Well a normal list is a mapping from natural numbers to values. To simplify matters for this post, we ignore the values themselves and consider only the domain of the mapping. For example, a normal list of length 3 will be represented as {0, 1, 2}. When encoded as linked lists, we can easily implement the following functions:

-

put(n, L): Add n values to the front of list L. A value at position m ends up at position n+m.

-

get(n, L): Remove n values from the front of list L. A value at position m ends up at m-n.

For example, starting with the empty list {}, we might put(5) to get {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} and then get(2) to get {0, 1, 2}. Note that these are pure functions returning new values rather that editing the existing list. I’m abusing notation, and what we’re actually computing is get(2, put(5, {})), which is equivalent to put(3, {}).

Now, a transfinite list is simply a mapping from ordinals to values, supporting the same functions. I made it up so don’t google it.

Starting with {0, 1, 2}, if we put(ω) we should get the list {0, ω, ω+1, ω+2}. As specified, we’ve put by n=ω, so each m in the list goes to ω+m. Now if we put(1), we get the list {0, 1, ω, ω+1, ω+2}. For example ω+1 goes to 1+(ω+1) = ω+1, staying put. Note that we can keep doing put(1) without moving any of the values past ω, which acts as a sort of separator between sub-lists. After any number of put(1)s, we can get(ω+1), yielding {0, 1}.

Note that transfinite lists will be “sparse” because we can’t actually add an infinite number of values to the list; we’re interested in finitary encodings. For example, the list {0, 1, ω, ω+1, ω+2} has holes at all natural numbers from 2 up. We might say that the length of a list is the largest number in the domain plus 1 (or 0 if empty), while the size is the cardinality of the domain. These coincide iff the list is finite and non-sparse.

Naive Implementation

Once the above example makes sense, take a moment to consider how we might implement this as a data structure. A first implementation is to store the derivative of the list, i.e. a normal list of gaps between values. So {0, 1, 2, 3, ω, ω+1, ω+2} would be represented as [1, 1, 1, ω, 1, 1]. This makes the implementation of put(n) trivial; we simply prepend n onto the derivative list. The implementation of get isn’t so complicated either:

get(n, [d, …L]) := if (n = 0) then [d, …L] else get(n-d, […L])

That is, we keep subtracting differences in the list from n until we reach 0. Note that this is a simplification in that it won’t quite work when n isn’t in the list, and we’ll eventually reach a call where 0<n<d. Using the example derivative list above with get(ω), we’ll compute:

get(ω, [1, 1, 1, ω, 1, 1]) = if (ω = 0) then [1, 1, 1, ω, 1, 1] else get(ω-1, [1, 1, ω, 1, 1]) = get(ω, [1, 1, ω, 1, 1]) = … = get(ω, [1, ω, 1, 1]) = … = get(ω, [ω, 1, 1]) = … = get(0, [1, 1]) = if (0 = 0) then [1, 1] else get(0–1, [1]) = [1, 1].

The resulting derivative list [1, 1] represents the list {0, 1, 2} as desired. Note that we must use “left subtraction” here. To see why, try get(ω+1) with the same list. After one step, we iterate on get with (ω+1)-1 which equals ω+1 with left subtraction, so n isn’t depleted and we eventually return [1].

Efficient Implementation

Now we’re ready for the interesting part. The above implementation works, but if we have many 1s in the derivative list before the ω, the algorithm will have to step through all of them, which seems wasteful. We might get around the problem temporarily by storing lists of derivative lists, letting us skip ahead to the next ω, but this only works for transfinite lists of lengths less than ω².

Let’s consider an implementation “efficient” if it can compute get(n, L) in time proportionate to the size of a reasonable representation of n. Note that like in my other list post, this is independent of the length of the list itself. Also note that since ω usually has a small representation, we should want the above example to run quickly, regardless of how many leading 1s there are in the derivative list.

The solution once again lies in the representation of ordinals with balanced parentheses, which I would argue is a reasonable representation, and which I explained in my other ordinals post. The trick is for get(n) to use the sequence of left and right parentheses describing n to guide a path through our data structure. Let’s skip straight to an example:

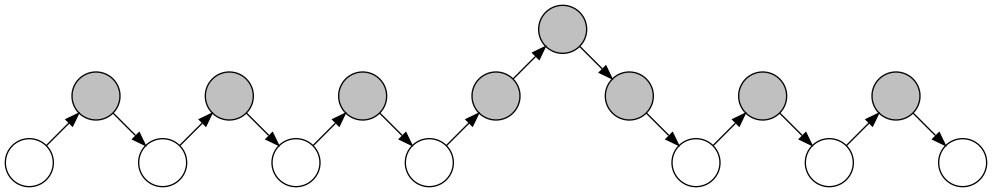

Recalling that the balanced parentheses representation of 1 is () and of ω is (()), the above can be seen as a depiction of the same difference list from above: [1, 1, 1, ω, 1, 1] = [(), (), (), (()), (), ()] = ()()()(())()(). Just tilt your head to the right and follow the sequence from bottom/left to the top/right. Left parens move left up the structure and right parens move right. The hollow nodes are where we might attach values, and the filled ones just connect them.

Clearly this doesn’t work yet. Trying to do get(ω) by following the path (()) will go off the path, but it’s clear how we’d wish to correct this:

Now doing get(ω) from any of the hollow nodes on the left will follow the path (()) and end up at the same correct node, yielding:

Cool, but can we actually build this structure when we do put(n, L)? Yep, easily! While we build a new path for n like (), we simultaneously follow the same path from the existing node for L. Whenever the path goes right, if the follow path has an edge going left, we add one in the build path to the same node.

For example, the diagram below depicts a put(1, L) using a path of (). The (dashed) build path follows the (bold) follow path, copying its (dotted) left edge to the topmost node.

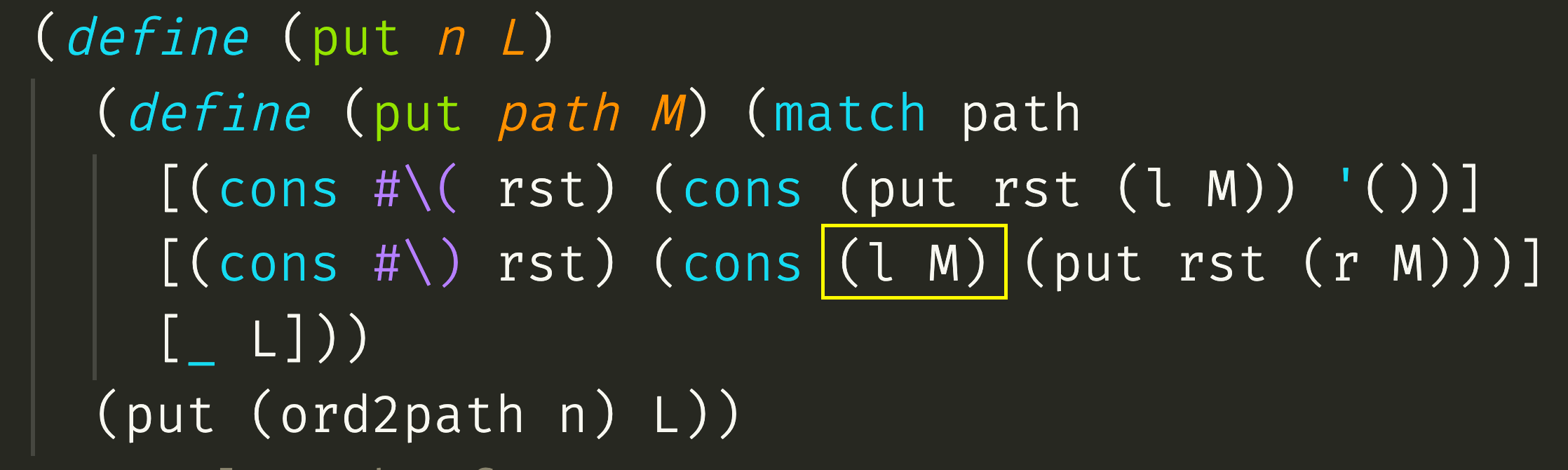

The implementation of put is shown below. The function ord2path converts an ordinal to a list of parentheses. The functions l and r return the left and right element respectively when passed a pair, or else return null. The yellow box shows where the build path copies the left edge of the follow path.

Example

I don’t have a proof that this works, so I’ll distract you with another intuition-building example:

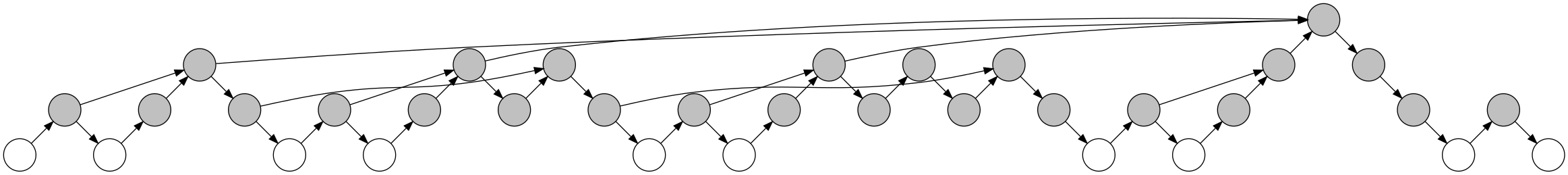

This represents the transfinite list {0, 1, ω, ω+1, ω², ω²+1, ω³, ω³+1, ω^ω, ω^ω+1} with the derivative list [1, ω, 1, ω², 1, ω³, 1, ω^ω, 1]. Note how the peak of the first 1 difference can be followed all the way to the peak of the ω^ω difference. Note also how the structure was built up from right to left without ever having to follow an unbounded number of edges, simply by following previous edges. If you’re concerned that some nodes are lacking left edges, notice that any such path would correspond to an illegal ordinal like ω^(1+ω). Now if we do a get(ω²+1) by following the path (()())(), we end up with:

In Practice

I chose to implement this in a Lisp-like language (Racket) because there are parentheses and pairs everywhere of course. In fact, nodes are just pairs, ordinals are represented with nested lists alone, and the translation from ordinals to paths and back is done with printing and parsing(!) respectively. The diagrams are generated with graphviz/neato.

The code is only a few dozen lines: https://github.com/asvarga/tf-lists